Is Technology Making Us More Productive?

You can see the computer age everywhere but in

the productivity statistics. – Robert Solow (1987)

As an engineer, I'm obsessed with productivity. My personal life is tracked in Notion lists and Evernote clips, and I've built numerous developer tools to make software development more optimized. Here in Silicon Valley, productivity is a hallowed concept embedded in the lore of engineers staying up late hours of the night in garages working on the next big thing. But, is there any evidence that technology is actually making us more productive?

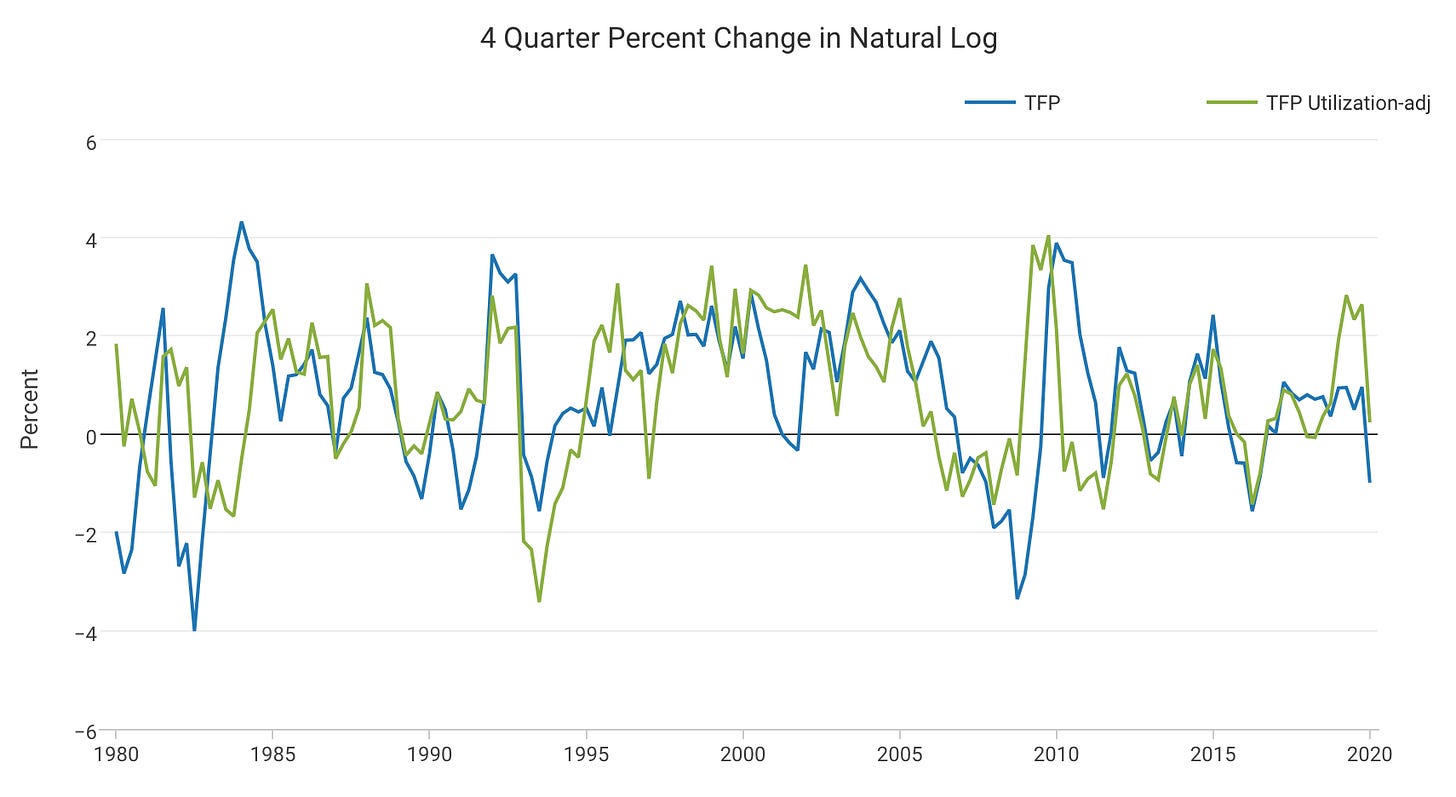

Measuring productivity is a difficult task. Macroeconomists don't attempt to measure it directly, instead, they measure something called total factor productivity (TFP), which is the residual that is not accounted for by capital accumulation or labor when calculating the growth rate of GDP output.

Macroeconomists and Silicon Valley both agree on one thing - productivity matters. One interesting discovery related to productivity is Paul Romer's endogenous growth theory, for which he won the Nobel Prize in Economics. The theory says that the most important driver of long-term economic growth is the investment and growth of ideas, which shows up in TFP.

However, when looking at the data, productivity in the US and around the world shows a concerning trend. Since the 1980s, productivity growth has been falling around the world and is even negative in many European countries. The fact that this trend lines up with the advent and mass use and distribution of the personal computer is the productivity paradox. Even in companies that invested heavily in software, productivity growth slowed down. At face value, this would suggest the counterintuitive result that software is not actually making us more productive. Why haven't these supposed productivity gains showed up in TFP?

Explaining the Paradox

Free internet services aren't directly measured in GDP. One explanation for the paradox is the mismeasurement of inputs and outputs. Google offers Search, Android, Chrome, and Gmail for free. The welfare and leisure time we get from using these products isn't directly measured in GDP. However, when researchers tried to measure this deficit, it was estimated that the productivity shortfall was $2.7 trillion in GDP loss from 2004-2016 - did free internet services really create this large of a consumer surplus? Another macroeconomist, Syverson, found that the slowdown in productivity wasn't correlated with technology production or usage, ultimately defeating this theory.

Profits are redistributed to certain firms, while technology as a whole is unproductive for the economy as a whole. This theory says that some firms are more productive with technology, while for others the investment isn't profitable. While you can find anecdotal evidence of companies purchasing SaaS products that are never fully utilized correctly, it's difficult to think that technology isn't ubiquitously productive for the majority of firms.

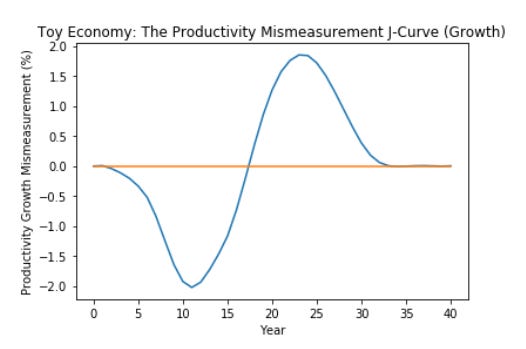

Technology takes time to diffuse and for firms to learn and adjust before it is productive. While companies like Notion may be a household name in Silicon Valley, the technology hasn't permeated many other regions in the U.S. The field of machine learning has seen huge steps forward in model performance and utility, but the infrastructure, tools, and libraries that can make the technology productive are still coming to fruition. One of the most exciting papers on this topic is The Productivity J-Curve by Brynjolfsson, Rock, and Syverson.

In this paper, the authors describe technologies they call "general purpose technologies (GPT)", which we might think of as building blocks such as TCP/IP, HTTP, deep learning algorithms, and other foundational API layers. They find that early on, we underestimate the productivity gains from these technologies because of all the complementary technologies that need to be developed for the GPTs to be fully utilized. From my own experience, I've seen how distributed machine learning has gone from being inaccessible to becoming a commodity. Now, it's significantly easier to reproduce cutting-edge machine learning research that requires thousands of layers and massive compute simply by using open-source projects like Tensorflow and Kubeflow and cloud computing.

If Brynjolfsson is correct, should we see a significant gain in productivity growth in the future, as machine learning and other foundational technology like Kubernetes become more accessible? As more people outside Silicon Valley use tools like Notion and Roam Research, will we see productivity growth in non-traditional industries other than technology?